Santa Clara River Valley (Photo Credit: Kent Kanouse/Flickr)

Open land and economic development can seem like they are in constant conflict, but new data proves that the two can actually function together seamlessly, bringing more “green”—money and nature—to California.

“We have such a huge opportunity to ask, ‘What do we want our community to look like in the future?’” said Karen Gaffney, conservation planning manager for Sonoma County. And by community, Gaffney is referring to California’s sprawling and lucrative ecosystem.

Gaffney works to preserve open spaces in Sonoma by documenting the economic benefits of growing and maintaining working landscapes. Working landscapes can include farmlands, wetlands, forests, mines and water basins, all of which equate to natural capital.

“I think people have a general understanding of the economic benefits of the environment, but they don’t have a full understanding of what agriculture and open spaces can provide,” said Gaffney.

And what they provide is highly valuable and necessary for a thriving ecosystem and economy in California. For example, the value of clean and safe drinking water, storm and flood risk mitigation, pollination, food distribution and tourism can add up to $1.6 – $3.9 billion every year which streams directly into the economy.

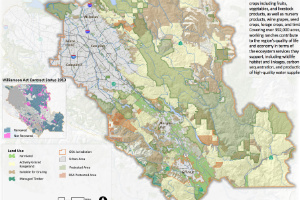

Those large numbers were discovered through the Santa Clara Valley Greenprint initiative, a project that uses technology to pinpoint an exact space that will make California the most money, essentially maximizing capital. The Greenprint uses data to map out valuable land spaces and see where they intersect to gain the largest investment. Greenprint identified ten working landscapes, which are now being maintained and protected.

Considering Santa Clara County, home to Silicon Valley, is the fastest growing county in California and expected to grow 36 percent in the next 30 years, open spaces will need protecting. Andrea Mackenzie is finding ways to protect the 63,000 acres of open land space that could turn into more roads and real estate.

“Ultimately a plan like this is dovetailing with statewide priorities, like conducting growth into cities where services can be provided rather than sprawling out into farmland”, said Mackenzie, general manager of the Santa Clara County Open Space Authority, an independent special district tasked with regional preservation. “We use it to communicate with other agencies to get partnerships. Together we can meet these goals.”

Working landscapes also equal the development of jobs, surprisingly, in cities. By maintaining working landscapes, California may see a whopping 272,000 jobs in the near future, 60 percent of which would develop in cities, says Glenda Humiston, USDA state director of rural development and co-chair of the Summit’s Working Landscapes Action Team. For example, instead of shipping products for processing out of state, companies could expand or startup to take care of that locally.

“The processing facilities belong in cities where they have infrastructure. This is an urban-rural partnership and that is what is really important”, said Humiston.

The Working Landscapes Action Team is working to ensure future generations have the proper tools, like good data and smart policy, to effectively evaluate working lands and also to bring light to the fact that California is sitting on a big economic opportunity. Humiston thinks that awareness of the value of working landscapes is shortsighted.

“There is so much angst when we try to figure out how to best use our natural resources and a lot of times folks don’t see what’s in it for them,” said Humiston.

And a lot of money is what’s in it for them. After all, who would have guessed that a piece of land could equate to billions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of jobs for California? And that’s something these organizations can share with the people in their regions by documenting the economic worth of working lands and proving the value of investment in conservation.