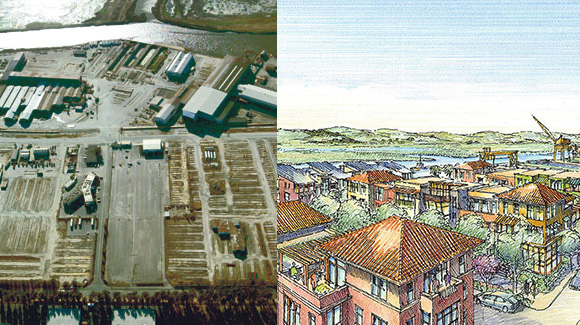

Archival aerial photo of Napa Pipe site and rendering of propopsed development (Photo Credit: Napa Redevelopment Partners)

The process, so common in California, began over ten years ago, with the closure of Napa Pipe, an old Kaiser Steel facility on the border of the city of Napa. In the tight confines of the agricultural valley, the 163-acre site offered a rare slice of undeveloped land that could be used for new housing—with enough space for almost 1,000 units along the Napa River, a ten-minute drive from downtown. The first housing project in the former industrial area was proposed in 2006.

A decade later—after years of hearings, studies, and disagreements over when and how to build out the area—there still aren’t any houses on the Napa Pipe site. If this sounds eerily familiar, it should. For as long as most of us can remember, California’s local governments and community groups have been sparring over housing responsibilities, even while tens of thousands of workers (in Napa’s case) spend hours each day sitting in traffic as they commute from out of town.

The Napa Pipe project, though, may be poised to become an exception to the usual housing rules. The Napa community has finally put the posturing and delays behind them—and as many as 945 units of housing will go up soon on the Napa Pipe site, thanks to a carefully crafted agreement between the city and county that could serve as a model for getting more housing projects approved faster and cheaper.

Napa Pipe’s prospects showed their first signs of changing in 2012, when the city and the county began negotiating a series of agreements over how to handle the property: The county, which had rezoned the site, wanted to count new housing units toward its Regional Housing Needs Allocation obligations under state law. The city, which would be responsible for providing services (including water) to the area, wanted a say in what the development would look like, how dense it would be, and how its nearly 3,000 residents would move between the site and the rest of the region.

Both parties agreed that the property would need to be annexed by the city. The question—a familiar one in jurisdictions across California—was how certain all parties could be that when the entitlements were issued:

- The project would get built in the way it was approved

- The ultimate development of the project would be consistent with city standards

- No further approvals would be needed that would further delay or undermine the development

The answer, in Napa, was a combination of two local policy innovations: the adoption of a new form-based code paired with a set of detailed design guidelines outlining the types of buildings that would be permitted in the development. (Editor’s note: The author was involved in this effort as Napa County’s then-director of housing and intergovernmental affairs.)

These new policy tools were designed to work in tandem with a development agreement reached in 2014 between the developer (Napa Redevelopment Partners LLC), the county, and the city that outlined the terms under which the project could proceed. In the agreement, the Napa Pipe site was divided in half, with the western portion devoted to high-density residential, open space, retail, restaurants, and a hotel—and the eastern portion reserved for a Costco. The agreement stipulated the number, location, and type of units, as well as the community benefits they would receive (e.g. parks and schools). Both the city and county adopted resolutions stipulating the development was in compliance with their land use plans.

All of this is fairly standard operating procedure. What made Napa Pipe different is that each of the parties also agreed that, so long as the development continued in a manner consistent with the terms of this agreement (aside from any minor amendments), individual projects could proceed without further discretionary approvals.

The developer, in particular, worried that the city’s design review process might still further delay the project by months or years—especially a City of Napa rule requiring projects with over five units to be issued conditional use permits. To overcome this hurdle, the city and county collaborated with a national firm, Sitelabs, on a set of form-based code and design guidelines that were intended to dramatically accelerate the last step of the approval process. The finished product was a 150-page document establishing the form and function for every single home or commercial building that could be developed on the site—from specific types of permitted townhome designs to acceptable lot coverages and setbacks.

So long as new housing projects are consistent with these new guidelines, administrative approvals will be granted for all new permits. When the time comes for builders to break ground on new units, in other words, they will only have to wait about three weeks to get a green light from the city—instead of the 8-12 weeks this can take under normal circumstances. Once the remaining environmental cleanup of the former industrial area is done later this year, Napa Pipe housing projects will go up faster than anywhere else in the county.

With housing unaffordability rising across California—and with groups like the CA Economic Summit highlighting the growing consequences of the state’s housing shortage—promising projects like Napa Pipe can’t be allowed to cost any more or take any longer. Form-based codes and design review guidelines are two helpful new tools more communities should be using to get housing developments across the finish line.

The good news is that these fast-track approvals may be catching on. Napa Pipe’s development agreement was modeled after a successful effort in 2010 to approve almost 4,000 units of housing on the site of a former military base outside Boston. Several major projects in California are also considering adoption of a similar approach, including San Francisco’s Pier 70 and Hunters Point Naval Shipyard projects.

Policy changes on this scale aren’t workable for every potential housing project, of course. The high costs associated with writing the code and design guidelines (close to $1 million for Napa Pipe) make it most suitable for projects of 1,000 or more units. This may mean new master-planned projects will be the biggest beneficiary.

Napa’s approach is still a giant step forward, though, and when the first projects break ground in 2018, it will be a positive sign that communities like Napa, after years of working at cross-purposes, can actually get housing built—quickly, cheaply, and without all the usual fuss.

Larry Florin is CEO of Burbank Housing